What Do You Know About Homelessness

Something that I took for granted in one section of "Some Thoughts on Kinesthesia Lounge Politics" that I realize not everyone knows or agrees with is that homelessness is fundamentally continuous with full general housing policy.

This is at odds with how it is normally synthetic in American politics, in which you lot have a discrete population of people who exercise not have a home and then a question of what to do about them. Every bit a last resort, this tends to become a police force enforcement question, but in essentially every city, there is also a social service provider community that is trying to help the homeless in not-punitive ways. So then you lot take a soapbox about the funding of social services and what boundaries police force enforcement should enforce. There are then micro-niche issues about how shelters for people experiencing homelessness should be run. And, at that place is a perennial conversation about root causes — the people sleeping on the streets are often suffering from addiction bug or mental health difficulties, and we possibly demand to straighten those issues out somehow or other.

These are all, I think, valid questions to ask in the sense that people demand to accept the world as they find it and deal with situations that exist.

Simply broadly speaking, I think it misconstrues the problem every bit a "homelessness" trouble with chief adjacencies to mental health, habit services, and police force enforcement. I think information technology'southward a housing trouble with primary adjacencies to questions similar "why was New York City'due south population falling even earlier the pandemic?"

Nobody goes there anymore, it's too crowded

The Covid-19 pandemic was unfortunate for many, many, many reasons, just for housing policy junkies, ane downside is nosotros wound up paying no attention to the 2019 NYC population decline since the following decline in 2020 was so clearly almost the pandemic. In 2021, there is sure to be a post-pandemic bounceback and a lot of stories about New York'south struggle to come back.

What happens in New York is always important both because it is past far America's largest city, but also because the overwhelming concentration of media at that place tends to mean bug are read through a New York City lens.

So the question of why people were fleeing NYC in 2019 — before the pandemic, before the school closures, before the ascension in the murder rate — should have been an analytically significant event. People can get out cities for all kinds of reasons, after all, but most of them would come down to "it became a worse place to live."1 Only what you expect to run into if somewhere becomes a worse place to alive is that the cost of living at that place falls thanks to low demand.

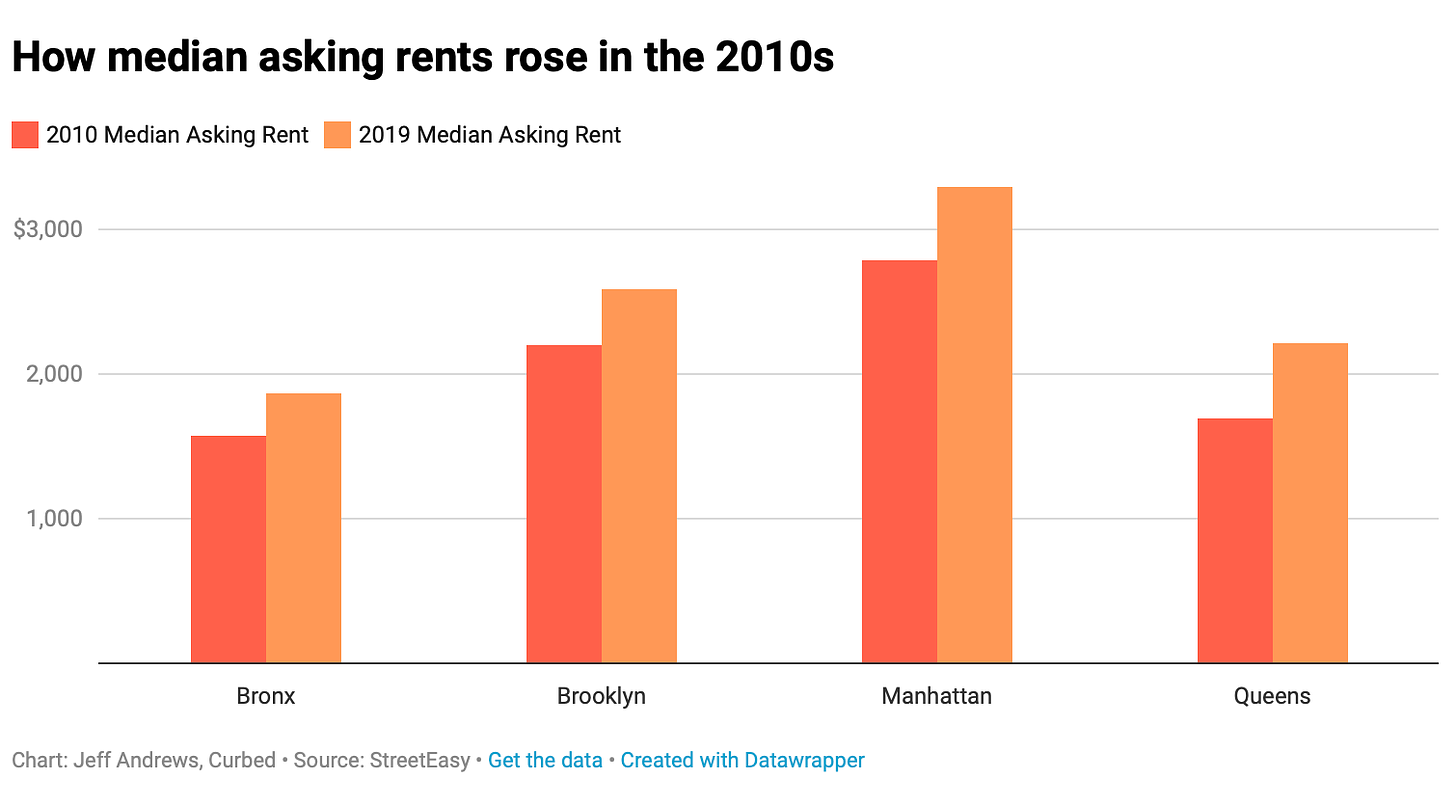

But what we actually observed was a potent increase in rents over the decade.

Rather than New York condign a worse place to live, information technology became a more expensive identify to live. Structure of new units did not keep pace with the increase in demand. So the population cruel as families who might have had 3 or four people living in a ii-bedroom apartment were replaced with childless professional couples, and wealthy people combined units to make larger dwellings for themselves.

Demand for housing is ascension but the supply does not rise at the same rate, so people get squeezed out and the city'due south population falls as people caput for cheaper pastures in the Sunbelt. Simply what if y'all're squeezed out of housing and you don't go out for somewhere else? Well, then you lot've got nowhere to live.

Homelessness is loftier where housing is expensive

Leftists often enhance the truthful-but-misleading factoid that the number of people experiencing homelessness on any given day is by and large much smaller than the number of homes that are unoccupied on whatever given day.

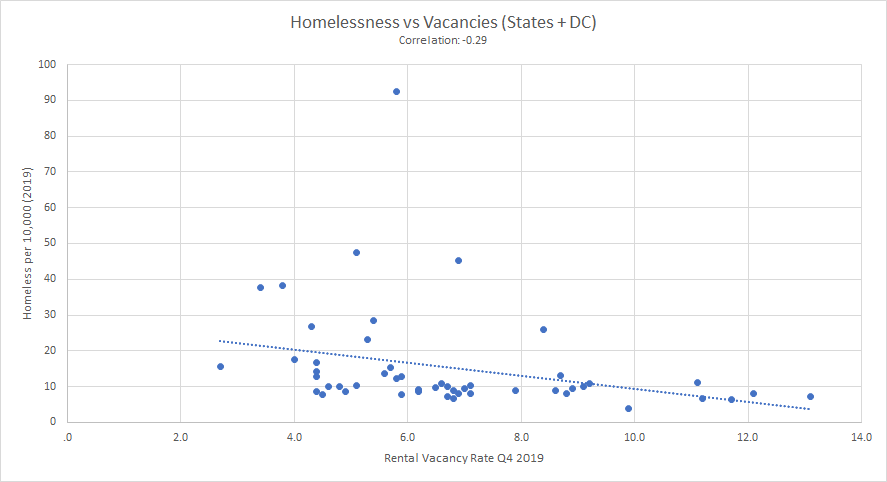

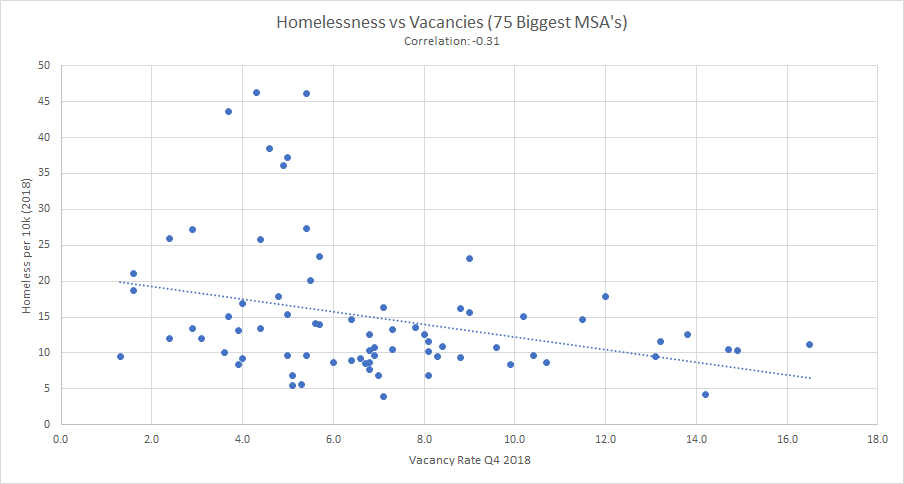

Only as we covered in "Homelessness and Vacant Houses," it'due south non the case that homelessness is high where vacancy rates are high. Indeed, it'due south the contrary — the vacancy rate is lower in places with more than homelessness.

Hither's an analysis looking at states:

And here'south one looking at big metro areas:

That's because unusually high levels of homelessness and unusually low levels of vacancy are both acquired past the same thing — scarcity of dwellings.

According to the United States Interagency Quango on Homelessness' 2019 count, there were roughly as many unhoused in New York state on a given solar day as in Texas, Florida, Pennsylvania, Georgia, and Illinois combined, despite New York having a much smaller population. That'southward because New York City circa 2019 was a huge engine of displacement, featuring net population losses and likewise people who, for whatever reason, got squeezed out without going anywhere.

We retrieve of the "homeless person" and the "moved to Due north Carolina to be closer to family unit and also to afford more infinite for the kids" equally two entirely unlike types of people. But information technology's a unmarried underlying phenomenon. And who ends up in which category will come downwards to a mix of luck, whether or not you do in fact have family in N Carolina, and whether or not the forces pushing you out of the high-price area come up on y'all slowly so y'all have time to programme.

The top six states for homelessness rates are New York, Hawaii, California, Oregon, Washington, and Massachusetts, which is basically just a list of states where housing is expensive. The highest homelessness rate in Texas is in Austin, which is the urban center with the well-nigh expensive housing.

More homes, less homelessness

I know it'south a picayune flake counterintuitive to people, but in a broad sense, the biggest thing nosotros could do to take a seize with teeth out of homelessness in the medium term is build more than luxury condos.

When I first started making the case for land use reform, we had two legs to our argument. One was bones economic theory — more supply equals less scarcity equals lower prices. The other was cross-exclusive assay — metro areas with laxer country use regulation see more structure and lower prices. But we tin can now add a 3rd leg to that analysis in terms of detailed empirical work. Here'south a adept roundup of five studies from the UCLA Lewis Center that they did in Feb, and in April, nosotros have "Local Furnishings of Big New Apartment Buildings in Low-Income Areas" and it says the same thing:

We report the local furnishings of new market place-charge per unit housing in low-income areas using microdata on large apartment buildings, rents, and migration. New buildings subtract rents in nearby units by nigh 6 percent relative to units slightly farther away or near sites developed later, and they increment in-migration from low-income areas. We show that new buildings absorb many loftier-income households and increase the local housing stock substantially. If buildings improve nearby amenities, the result is not large plenty to increase rents. Assiduities improvements could exist express because most buildings go into already-changing neighborhoods, or buildings could create disamenities such as congestion.

The fact that the new buildings are non "affordable housing" in the regulatory sense doesn't mean that they have no impact on affordability. Nor does the fact that a person existing on the margins of homelessness would exist unable to live in such a building alter the fact that allowing their construction reduces homelessness past increasing the affordability of other units.

With this new empirical work, I'one thousand increasingly confident saying that the key thing really is to legalize every bit much market-charge per unit housing as possible. Not because there'south anything wrong with subsidized housing. But because market place-rate housing generates taxation acquirement by bringing in new affluent residents, and that revenue can be used to finance an affordable housing trust fund or new public housing or whatever else you desire. Cities looking to tackle homelessness should upzone for more market-rate structure and enhance their existing social service spending in line with the increased revenue.

But they should too take a look at the range of edifice types that they allow.

A bad house is better than no house

Paytung Chung wrote a post about the history of housing in the District of Columbia that has stuck with me ever since I first read it viii years agone:

The 1951 sci-fi classic "The Day the Earth Stood Withal" inadvertently shows u.s.a. how. Klaatu, a level-headed extra-terrestrial emissary, escapes captivity at Walter Reed Ground forces Medical Center. He wanders downwardly Georgia Avenue, away from not-nevertheless-nuclear-weapon-free Takoma Park, and attempts to disappear into everyday DC.

To do so, Klaatu checks into a boarding house at 14th and Harvard in Columbia Heights. Each room houses one or two people, and equally such there'south scant privacy to be had: everyone overhears everything.

This is convenient for Klaatu, who knows little of Earthlings' simple means, only probably annoying for the Earthlings. Conditions similar these were common in DC homes at the time.

And, indeed, this was the typical mode of accommodation for a non-wealthy, not-married person in the Us who wanted to get out of mom and dad's house and work in the big city.

These Library of Congress photos show life in a D.C. boarding business firm:

You can run into two beds in a tiny room here. In a boarding house, yous would share a bathroom with others on the hall and employ a shared dining room.

In America today, this persists as a fashion of accommodation for college students, simply it'southward largely vanished.

That's mostly for skilful reasons. Thank you to widespread motorcar buying, there'southward more than space to build homes. And because the Usa is a lot richer than it was in Klaatu'south time, we can afford to build larger structures. But obviously not everyone tin afford to alive in a mod one-sleeping room apartment or there wouldn't be a homelessness problem to blog about. The issue, as is common in American planning, is that we took something that'south normal (people want a place to park their automobile, people want their ain bathroom in their domicile) and we made it mandatory without regard to its implications for affordability on the margin.

I used to think of this as largely a example of unintended consequences or skilful intentions gone awry. But then I constitute the American Guild of Planning Officials' 1957 guidance on rooming houses and they are actually pretty clear that the regulation is pretextual.

They open up by quoting an October xviii, 1957 editorial in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch which says:

If rooming houses are permitted to spread to the city's one- and two-family neighborhoods, there is non much use in talking dauntless words virtually fighting bane. Rooming houses are not compatible with ane- and two-family districts. When the rooming houses come up in, the families move out — and the whole area starts down hill. If St. Louis is to retain its many fine family neighborhoods, the rooming houses will take to be kept where they vest.

And the report agrees that "even under the strictest codes, rooming houses are out of identify in some neighborhoods." Merely they continue to further argue that in addition to using zoning to continue boarding houses out of single-family districts, cities can use minimum quality regulations to keep out undesirable types even where they are allowed:

Zoning is not the only tool available to command the blighting effects of rooming houses. Housing codes in an increasing number of cities require that decent — though often minimal — standards exist maintained in them. As well protecting the roomers, enforcement of these codes can do a nifty deal to assure that rooming houses exercise not harm districts in which they are properly located.

The study notes that "many roomers are real down-and-outers, and the temper of a rooming house in which they predominate is probable to be bleak" and complains that "hundreds of zoning ordinances have loopholes that permit grouping living arrangements."

Information technology took a while, but over the generations, the planners accept been very successful at more often than not eliminating the accommodations for down-and-outers2 with the event that if you are down and out in a metropolis where real estate is expensive, you terminate upward on the street.

Up from homeless shelters

Right at present the state-of-the-art goal in well-intentioned policymaking is to attempt to build more homeless shelters and so that people who don't have homes aren't sleeping rough.

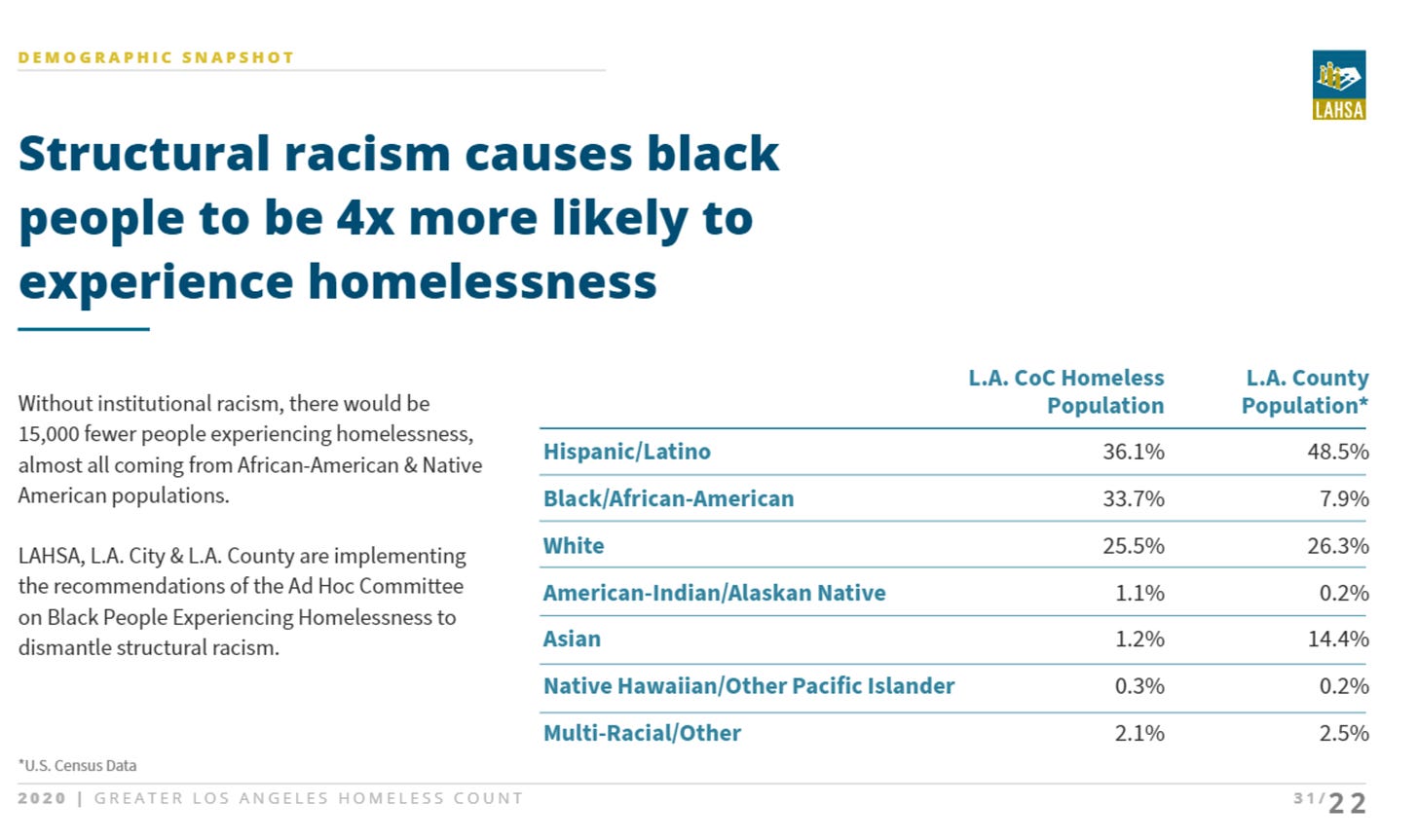

A federal judge in Los Angeles is even attempting to require the urban center to provide shelter space for all of the thousands of homeless Angelenos living in Slip Row. The city, of form, has no capacity to really exercise this and is appealing the decision. The argument made by the guess is that homelessness in Los Angeles is racist, due to what you lot can see here is an overrepresentation of African Americans among the unhoused.

This seems a lilliputian far-fetched as a legal theory, especially given the conservative majority on the Supreme Court. In general, a slight majority of those experiencing homelessness are white, and the indigenous group that well-nigh disproportionately suffers homelessness is Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders, which is pretty conspicuously because they overwhelmingly live in Hawaii, a state with very expensive housing.

Regardless of that legal theory, the irony of the homeless shelter is it completely replicates all the problems with the boarding firm — the living conditions are not good and the neighbors regard it equally an undesirable state use — except at the public's expense and without the residents having the dignity of a place of their ain where they can shop their things.

It'south likely that even if we fixed all the land-use problems, there would nevertheless be some need for social chapters to provide this kind of emergency shelter. But in that location's no good reason to have such a gap between the crappiest apartments for lease and the shelter. We ought to let the full spectrum of market phenomena — including plenty of shiny new buildings for rich people and the subdivision of older buildings into boarding houses for down-and-outers and the occasional visiting conflicting.

Ane central bespeak is that nigh people who find themselves down-and-out due to job loss, a breakup with a partner, a fight with family unit members, a dispute with a landlord, an emergency expense, or whatsoever other problem will in fact get their anxiety under them and bounce back. Simply it's much harder to bounce back if you sink into a situation where you're exposed to the health and safety issues of being on the street, don't take easy access to a shower and then you can be presentable when looking for work, and don't have whatever place to go on your stuff.

More of everything

At present, what'due south true is there are people out on the streets this week and they need help at present. What I'chiliad talking about hither are generally mid-range solutions, non crunch measures.

That said, we actually ought to fix this trouble rather than beingness stuck perennially in crisis fashion. These are locally focused bug, so the precise nuances of the relevant zoning codes and planning terrain will vary profoundly. But hither'due south a great account of the rise of Single-Room Occupancy (SRO) dwellings in New York — that's the higher density equivalent of D.C.'south rooming houses — and their deliberate devastation, which ends up a call to lift the rules that forestall the construction of new ones. That's something both Kathryn Garcia and Andrew Yang take talked virtually, and they're correct.

But I exercise want to emphasize that far and abroad the best utilize-instance for SROs, rooming houses, and other subprime rental housing types is in a context when a lot of fancy new buildings are being built.

Under the current economics, it doesn't brand a ton of sense to invest a large sum of capital in constructing a brand new boarding house. And if you practice, information technology would be an upscale boarding house targeting frugal recent higher grads, not down-and-outers. At that place's aught wrong with that idea — housing is housing, every bit I've emphasized, and the markets are all connected — but it wouldn't "bring back" the cheap housing of yore.

What brings back that very cheap housing is that in the context of lots of new high-end development, at that place'due south less demand for the older housing stock. Some of it will get renovated to exist shiny and new over again. But historically, the very cheap housing came from subdividing old units that nobody really wanted in order to serve an fifty-fifty-more than-downscale market.

Now don't become me wrong! I'thousand not saying that living in some flophouse is the housing utopia or the futurity of housing for everyone. The primary reason we no longer have lots of people living ii-to-a-room in units with no bathroom is that we're not living through the Groovy Depression and World War Two anymore. Big, modernistic American houses are great. And we should try to accept full employment and a generous welfare state and all the other good things that make information technology possible for people to savour high living standards. Simply in the United States today, even equally most people accept housing that is much better than Klaathu'due south boarding firm, some people are as well poor for their housing and our current programme is to offer them something much worse instead.

Source: https://www.slowboring.com/p/homelessness-housing

0 Response to "What Do You Know About Homelessness"

Post a Comment